ECOWAS: A Market Too Big to Work

- 2 days ago

- 4 min read

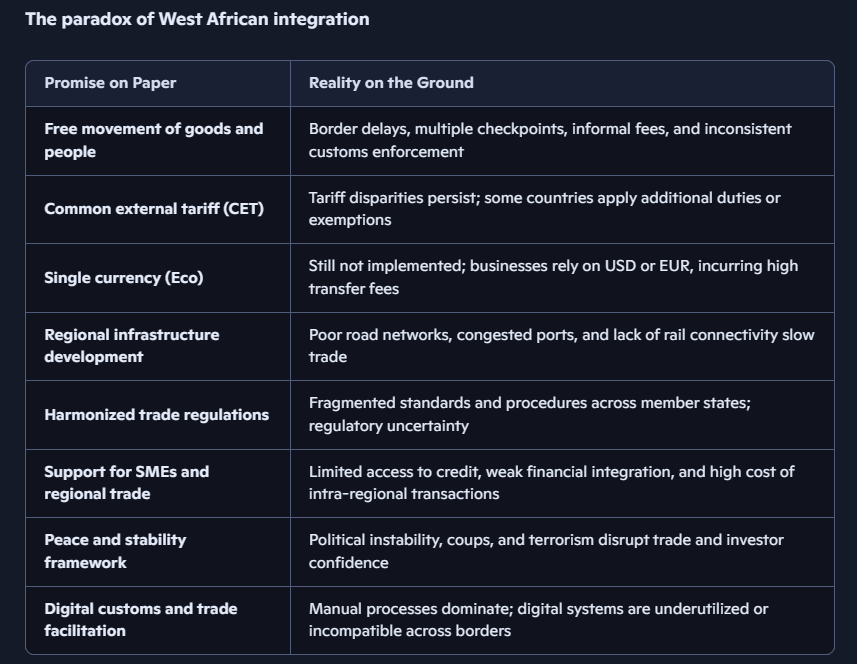

West Africa today presents a paradox that should trouble any serious observer of regional economics. On paper, established in 1975, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is a giant: now twelve active members, a population of over 420 million people, and a combined GDP exceeding $760 billion.

By contrast, the newly formed Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger—represents barely 74 million people and less than $50 billion in GDP. Yet while ECOWAS, with its demographic weight and decades of institutional history, struggles to deliver efficient transactions and meaningful integration, AES has moved with startling speed to build institutions, reroute trade, and project sovereignty.

One bloc is thriving; the other, despite its size, is faltering.

For businesses like Organic Trade & Investments (OTI) in Ghana, the frustrations are palpable. ECOWAS’s promise of a common market is undermined daily by costly bank transfers, a direct consequence of the region’s failure to implement its long‑promised single currency, the Eco. Transactions across borders often require routing through European or American banks, piling on fees that eat into already thin margins. Infrastructure gaps compound the problem: poor roads, congested ports, and unreliable rail links make moving goods across ECOWAS borders far more expensive than the theory of “free movement” suggests. For a company exporting shea butter or African black soap, the cost of logistics can outweigh the profit, turning opportunity into frustration.

Meanwhile, AES has acted decisively. Within months of its creation, the bloc announced a Confederal Investment and Development Bank, designed to finance infrastructure and trade corridors. It has pivoted trade routes toward Morocco’s Atlantic ports, giving landlocked members a lifeline to global markets. AES’s leaders, sharing language, political alignment, and urgency, have cut through the bureaucratic inertia that paralyzes ECOWAS.

Their smaller scale has become an advantage: fewer voices, faster decisions, clearer priorities.

ECOWAS’s defenders point to achievements: peacekeeping missions, tariff reduction protocols, and EU‑funded programs that strengthen governance and trade competitiveness. Indeed, the European Union remains one of ECOWAS’s largest financiers, underwriting integration projects and security frameworks. But dependency on external funding has bred a culture of process over progress. Language divides—Francophone, Anglophone, Lusophone—add layers of translation and legal complexity that slow harmonization. The result is a regional giant that cannot move with the agility its businesses demand.

ECOWAS is estimated to lose billions of USD annually due to poor infrastructure and trade inefficiencies, with intra-regional trade accounting for only about 12% of total trade. ECOWAS still lacks a unified digital customs system, leaving traders to contend with manual processes and inconsistent border protocols that create costly delays and invite informal fees. These inefficiencies discourage cross‑border commerce and erode confidence in regional integration. The irony is stark: while official reports project ambitious trade flows, ECOWAS’s own statistics reveal a persistent gap between promise and reality, underscoring the systemic failures that continue to stifle the region’s economic potential.

Premium Cocoa Liquor / Cocoa Mass from Ghana (1MT)

$8,400.00

Buy Now

You really cannot fault Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso for walking away from ECOWAS. How long can any serious leader afford to sit idle in a club that moves at a glacial pace, while the urgent task is to build a nation and deliver results? If you know exactly what must be done, why remain in a room where no one takes you seriously and where your supposed partners are the very obstacles to your progress? Ironically, the most elegant revenge is not protest or complaint—it is to leave, chart your own course, and succeed on your own terms.

The anger of entrepreneurs is not abstract. It is the lived reality of exporters who must navigate punitive border tariffs within ECOWAS, endure endless customs checks, and lose days moving goods from Nigeria to Ghana. What should be a straightforward regional transaction often becomes a logistical nightmare, with trucks idling at borders while paperwork is processed and informal fees extracted. The irony is striking: it is frequently cheaper and faster to ship a container from Ghana to Europe than to move goods across West African borders. For companies like Organic Trade & Investments (OTI), which can supply hundreds of tons of shea butter monthly, the constraint is not production capacity but the transactional inefficiencies baked into ECOWAS’s system.

100% Gluten-Free OTI Fonio Flour (100 kg)

$455.00

Buy Now

The paradox is stark. AES, with a fraction of ECOWAS’s population and GDP, is building institutions and trade corridors at speed. ECOWAS, with all its resources and external support, remains bogged down in bureaucracy, political instability, and the absence of a common currency. The lesson is clear: size without efficiency is a liability. Unless ECOWAS confronts its structural weaknesses—harmonizing customs, accelerating monetary integration, investing in infrastructure—it risks becoming irrelevant, a regional giant unable to serve its own businesses.

For West African entrepreneurs, the choice is increasingly between frustration and flight: remain trapped in ECOWAS’s expensive, fragmented system, or look to smaller, more agile blocs like AES for inspiration. The future of regional trade may well depend on which path they choose.

Unrefined Natural Beeswax Ghana & Tanzania (25 kg)

From$187.50$300.00

Buy Now

Perhaps the real problem is that ECOWAS members and business owners in the region are simply not angry enough. Flashy reports and impressive statistics look good on paper, but they mask a harsher reality: inefficiency, high costs, and endless delays. For many, finding a way around the system has become the norm, a quiet resignation to dysfunction. But for companies like Organic Trade & Investments (OTI), resignation is not an option. What we demand is not another glossy communiqué, but a genuine transformation—one that restores the sovereignty of the West African economy and finally delivers the integration that has been promised for decades," Esthy Ama Asante, CEO/Head of Business Development (OTI).

Comments